A popular eatery in town has fun asking customers to identify their orders by answers to questions and not by name. One’s order may be identified by The Beatles if the month’s question is “What is your favorite band” or by “Main Street” if the question is “On what street did you grow up?” This month’s question is, “With whom would you most like to have lunch?” Being there with my wife, I knew the correct answer on that occasion. I have a hunch, though, that most people populated their answers with the names of famous people. Fame and celebrity dictate our interests.

And our reading choices. And that can be a shame.

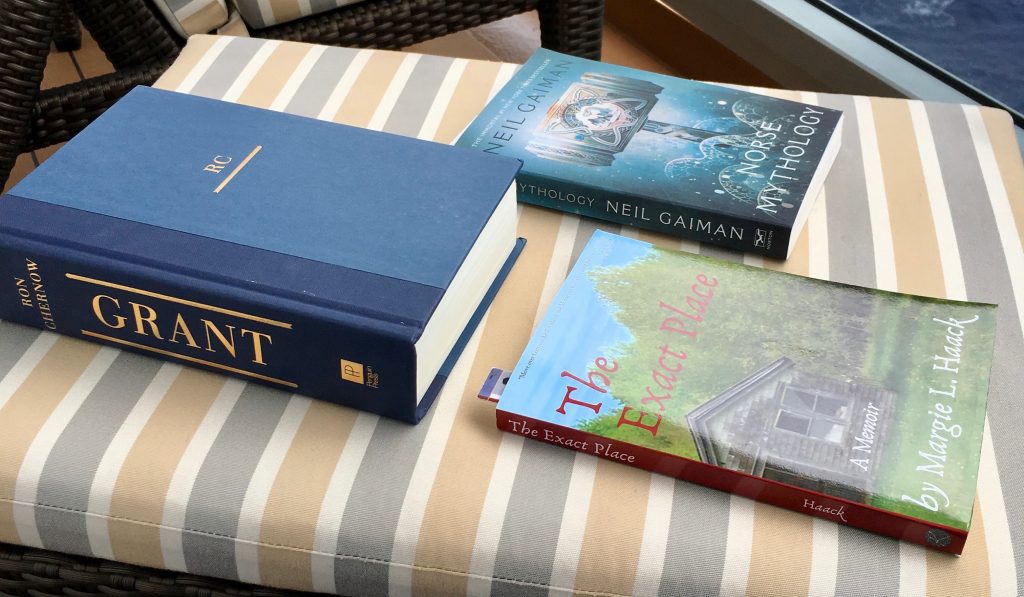

Faced with a choice of what to read recently, my choices narrowed to three: Ron Chernow’s biography, Grant, Neil Gaiman’s retelling of Norse mythology titled, not surprisingly, Norse Mythology, and Margie Haack’s memoir, The Exact Place.  Chernow wrote the biography that inspired Lin Manuel Miranda to create the Broadway hit Hamilton. Gaiman is the masterful storyteller both dark and delightful behind movies as diverse as Coraline and Stardust. And if we ask “Who is Margie Haack,” Wikipedia has no idea. Some know her as one of the key persons, with her husband Denis, behind a ministry called Ransom Fellowship. If fame was the deciding factor in my choice, Haack would not be in the race.

Chernow wrote the biography that inspired Lin Manuel Miranda to create the Broadway hit Hamilton. Gaiman is the masterful storyteller both dark and delightful behind movies as diverse as Coraline and Stardust. And if we ask “Who is Margie Haack,” Wikipedia has no idea. Some know her as one of the key persons, with her husband Denis, behind a ministry called Ransom Fellowship. If fame was the deciding factor in my choice, Haack would not be in the race.

To help my choice, I read the first ten pages of each.

Fame be damned.

The Exact Place winsomely tells Haack’s story of being raised by her mother and stepfather on a farm in a piece of rural northern Minnesota that should be Canada. The family’s house gave up no floor space for bathroom facilities (those being conveniently located in a separate building) but it was still small for a family of eight. The neighbors were memorable, some for their primness, some for their libertine tendencies, some for the terror they would bring. All the delights and hardship of such a life are lovingly told. Life, death, love, and bringing the horse into the house. Lack was normal, family ties were tight, and life was mostly okay.

Mostly.

There is an ache in these pages as she reveals her deep longing for the love of a father. She carefully unfolds this longing and weaves it through the story of her spiritual awakening, finding in God the love her heart was unable to find elsewhere. She lets her stories reveal this longing, its frustration and its satisfaction, without any tone of preachiness. Content with gentle nudges she helps us see the longing to be known and loved we all possess. I felt befriended and confided in, not lectured. There is power in that.

At times, fame is deserved. I’m now reading Grant and it is worth the praise it brings for Chernow. But lack of fame is not necessarily a reflection on quality. The Exact Place is s a wonderful book that was agented and rejected by thirty-five publishing houses before being given life by Kalos Press, a small independent publisher. I get that larger publishers must base their decisions on what will sell. They know that a book such as this by a relatively unknown, though profoundly gifted, author would not sell in the numbers they needed. And so they passed on giving it the kind of visibility they could give.

But this is our fault and not theirs. As readers we flock to the well known often over the well written. We prefer the Chernows and Gaimans and neglect the Haacks. And we are all the poorer for it.

me to push my writing to a larger platform. Such urgings stir something inside of me which I sometimes ignore. Other times, I feed them, as I did in April by attending the

me to push my writing to a larger platform. Such urgings stir something inside of me which I sometimes ignore. Other times, I feed them, as I did in April by attending the  The sabbatical will launch this Friday, April 6, with a party at the church for the congregation and all who have some relationship with the church or with me. A food truck will feed us, and a bounce house will swallow the children. Capping the evening, magician Marc Vergo will make the children disappear (or at least entertain them for 90 minutes) and the adults will enjoy a concert by the Jimmy Buffett tribute band,

The sabbatical will launch this Friday, April 6, with a party at the church for the congregation and all who have some relationship with the church or with me. A food truck will feed us, and a bounce house will swallow the children. Capping the evening, magician Marc Vergo will make the children disappear (or at least entertain them for 90 minutes) and the adults will enjoy a concert by the Jimmy Buffett tribute band,

In June, seeking a time of renewal, I’ll spend a week at the

In June, seeking a time of renewal, I’ll spend a week at the

ea that a pastor is called to ‘run’ a church. He believes that the adjective ‘busy’ modifying ‘pastor’ should grate against our ears with the dissonance of ‘adulterous’ attached to ‘husband.’ He invites pastors, who have been culturally set up to rise and fall with the numerical success of their congregations, to return to their calling to shepherd, to pray, and to preach.

ea that a pastor is called to ‘run’ a church. He believes that the adjective ‘busy’ modifying ‘pastor’ should grate against our ears with the dissonance of ‘adulterous’ attached to ‘husband.’ He invites pastors, who have been culturally set up to rise and fall with the numerical success of their congregations, to return to their calling to shepherd, to pray, and to preach.

The slippery slope is, to many, a place no one committed to orthodoxy and historic Christian doctrine should ever be found. But Brother Martin never got that memo. So with a few quick strokes of the hammer, he ventured onto it. And yet we honor him five-hundred years later while we excoriate others who follow in his footsteps today.

The slippery slope is, to many, a place no one committed to orthodoxy and historic Christian doctrine should ever be found. But Brother Martin never got that memo. So with a few quick strokes of the hammer, he ventured onto it. And yet we honor him five-hundred years later while we excoriate others who follow in his footsteps today.