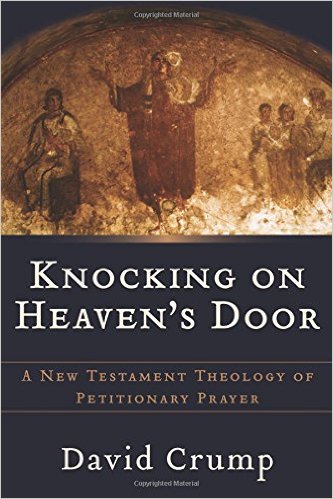

[This is a post in our ongoing series looking at the themes raised by David Crump in his book Knocking on Heaven’s Door: A New Testament Theology of Petitionary Prayer. We began this series here.]

❦

Years ago, I heard a man speak whose church had grown phenomenally. He attributed this growth to his commitment to spending hours daily in prayer, a commitment in which his church had joined him. A correlation was drawn between the number and persistence of people praying and the success of the church’s ministry. I was moved by the man’s faithfulness. I was challenged by his model. But I was never able to duplicate his devotion or his success. I am left to wonder: if I’d prayed one more day or had one more person join me, would we have tipped the scale in our favor?

What, that is, is the price of a miracle? Or is that even a proper question?

Some have read Jesus’ parables in the gospel of Luke (chapters 11 and 18) to suggest that prayer not only requires a special quantity of faith but as well particular investments of time, repetition, and emotional fervor. And such quantification seems to put a price tag on the miracles we seek. Is it really true that what God will not do if only ten are praying he will do if there are eleven or twenty? To have many praying, and praying long and hard is a good thing. But the line between doing what is good and attempting to manipulate God can be invisible to us if we are not careful. Crump unpacks these parables and in so doing helps us see our way beyond this creeping mechanistic view of prayer.

The point of the parables of the friend to who seeks bread from his neighbor at midnight (Luke 11) and the widow before the judge (Luke 18) is not that we can with our persistence irritate God into action. Rather, the point is that we should come to God at any time and with whatever need without shame and without hesitation.

We are to let nothing prevent our bringing our petitions to God. We will be persistent and we will pray without ceasing because we care about the matter at hand. But we do so not to pay a certain ‘price’ for a miracle. Our Father is always and ever willing to hear and to give what we most need.

The encouragement of these passages is to pray. We are encouraged to pray not so as to up the ante against God so that he must respond, but to pray knowing that he loves to give good gifts to his children, even when all we can see is darkness. Faithfulness in prayer is what is encouraged, and faithfulness is always more precious than a mechanistic persistence. The child who asks and asks and asks her father for a snake will not get it. But the child still asks, and the child will get what she most needs. But she asks not to up the pressure on one who will not give, but she asks simply because he is her father.

“The point is this: will I continue to bring my life before God in prayer when all tangible, empirical—and even all personal, experiential—evidence demands that I abandon prayer as worthless?” (page 88)

I want my answer to be, “Yes.”

❦

friends, both retired professors of literature and therefore assumed to have some insight into these things, the conversation turned to Dickens. This sounds like a stuffy conversation, I suppose, but it wasn’t. My wife had said how much she disliked Bleak House, that she only got a ways into it before she had to stop. She was relieved to find out that both of our friends found that book to be, well, ‘bleak’ as well. So we asked them for their favorite Dickens, and they agreed on (if my memory is correct)

friends, both retired professors of literature and therefore assumed to have some insight into these things, the conversation turned to Dickens. This sounds like a stuffy conversation, I suppose, but it wasn’t. My wife had said how much she disliked Bleak House, that she only got a ways into it before she had to stop. She was relieved to find out that both of our friends found that book to be, well, ‘bleak’ as well. So we asked them for their favorite Dickens, and they agreed on (if my memory is correct)  But is prayer a weakness because it is hard and unnatural for us, or do we find ourselves weak in it because of a misconception of what it is to be? If one trains to be a painter using a faulty and impossible standard, even though he may be good he will judge himself to be weak because he is using erroneous evaluative criteria. Perhaps we are overly critical of our practice of prayer because we are building our critique upon a false model of prayer.

But is prayer a weakness because it is hard and unnatural for us, or do we find ourselves weak in it because of a misconception of what it is to be? If one trains to be a painter using a faulty and impossible standard, even though he may be good he will judge himself to be weak because he is using erroneous evaluative criteria. Perhaps we are overly critical of our practice of prayer because we are building our critique upon a false model of prayer. So when I passed a man in my neighborhood the other day who was walking his dogs, I said, “What you are doing looks like a lot more fun than what I’m doing.”

So when I passed a man in my neighborhood the other day who was walking his dogs, I said, “What you are doing looks like a lot more fun than what I’m doing.” In the movie

In the movie

It seemed like a good, though drab, way for the mall to attract the attention of passing motorists.

It seemed like a good, though drab, way for the mall to attract the attention of passing motorists.