Recently I was approached by a woman who was reading, or attempting to do so, Marilynne Robinson’s novel Gilead for a book discussion group. The group had chosen the book upon my recommendation, so her considerable frustration with the book was focused on me.

“Tell me why it is you are making me read Gilead.”

“I’m not making you read it.”

“I know. But you must have some reason for recommending it, something we’re supposed to see in it. But I’m just not seeing it.”

Her conclusion was that she was simply too stupid to ‘get’ it which, obvious to all who know her, is by no means the case. I suggested she stop reading something she doesn’t enjoy, but she is of that stock that will plow to the end of the row no matter how many stones lie in the path.

I have yet to hear whether she has completed it. But the conversation raised a good question. Why would I recommend this book? Since I was nearing the end of my own (second!) reading, I was in a place to consider it.

❦ ❦ ❦

Gilead is the name of a small town in Iowa, the home of the Reverend John Ames, the elderly pastor of the local Congregational church, a church served previously by his father and his grandfather. Though in his 70s, Rev. Ames has a seven year-old son, his only child. He knows that his time with his son will be brief and not like that of other fathers. He sets out, therefore, to write a letter to convey something of his heart and history to a son with whom his time will be short. The book is this letter.

This father’s desire is to say to his son what needs saying. He wants to give him not only a sense of his history, but some direction for his future. He recounts stories, and sometimes personal or theological reflections on those stories. Through it, Rev. Ames wishes to honor and bless his son and leave him an enduring legacy.

❦ ❦ ❦

Great books invite multiple visits yielding fresh treasures with each visit. Gilead does not disappoint.

My first reading impressed me with wonder at the care and sensitivity with which the author, a lay female, had drawn the character of her protagonist, a male pastor. [I commented on that first reading here.] She sketches him with insight and care neither magnifying his weaknesses nor obscuring his sins. In John Ames, we see reflected the best that can be said for those whose desire it is to care for the souls of others while trying to make sense of his own. In him I see those many I’ve been privileged to know and observe, pastors rarely noticed by the world they faithfully serve.

When the spotlight normally falls on pastors, it is because of their exceptional gifts or prodigious foolishness. The ordinary faithful and flawed pastor (of which there are many) goes largely unnoticed. To find a pastor so sympathetically and accurately portrayed in a novel so widely acclaimed is a wonder which alone makes reading the book worthwhile. It gives honor to countless men and women who quietly and faithfully serve Christ in such undramatic but substantive ways.

My second reading, however, has pushed the impressions of the first to the side. Larger themes, noticed but unconsidered in the first reading, have emerged. The book brims with reflections on fathers and sons and the relationship between them. How do older generations bless the younger? Or, as it may sometimes be, curse them? How do younger generations genuinely honor the older? How can the powerful impact of the generations be navigated so as to possibly maximize blessing? Good art raises and rarely answers questions. Fiction creates a parallel world by which we can measure our own.

The book also addresses the struggle between belief and doubt. Faith is never taken for granted or shown to be an easy thing. Doubt wells up with differing levels of intensity in different characters. Are some of us meant to believe and others meant not to believe? Do we freely choose belief and unbelief? Pastor Ames wrestles with his faith mightily and is troubled by the doubts of others, particularly his friend’s son Jack. In Jack, he sees an inverse reflection of himself, and it troubles him.

Fathers, sons, faith, doubt, and through it all grace. Grace displayed, lived out, and, sometimes, rejected.

❦ ❦ ❦

Huckleberry Finn introduces the novel titled after him by threatening to shoot anyone trying to find a plot in the book. Those attempting to find a plot in Gilead might wish to shoot the author. The plot is revealed in a non-linear fashion. A story is told of a life well-lived, intersecting and impacting the lives of others in a profound way. There is conflict; there is climax; there is resolution. It develops slowly and erratically and is meant to be savored, not devoured. First one, and then another character is illuminated, as then, in their reflection, are we. And that is good.

Or it can be.

I’m glad that my friend is diligent and will finish the book. I hope she grows as fond of the Reverend John Ames, and of his creator, as I have. I hope she thanks me for ‘making’ her read it.

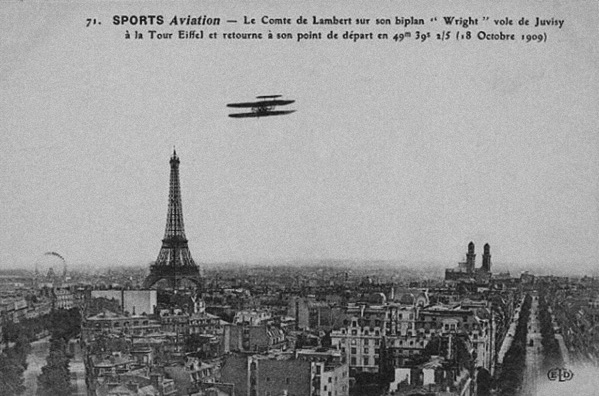

interest in the sons of Dayton for whom the air force base was named. With the release of David McCullough’s book The Wright Brothers, I have become interested. A good storyteller does that. He compels one to become interested in what interests him.

interest in the sons of Dayton for whom the air force base was named. With the release of David McCullough’s book The Wright Brothers, I have become interested. A good storyteller does that. He compels one to become interested in what interests him. Kidd tells Whitefield’s story with care and insight.

Kidd tells Whitefield’s story with care and insight.