Eric Metaxas’ massive 2010 biography of German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer (Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy ) was received so favorably that Christianity Today could report that six months after its release it had sold 160,000 hardcover copies, even though published by the American evangelical publisher Thomas Nelson. (It is still selling at a volume that keeps it in the top 1000 of all books sold on Amazon.com.)

) was received so favorably that Christianity Today could report that six months after its release it had sold 160,000 hardcover copies, even though published by the American evangelical publisher Thomas Nelson. (It is still selling at a volume that keeps it in the top 1000 of all books sold on Amazon.com.)

Evangelical reviewers were effusive in their praise. A reviewer in Books and Culture introduces it as a “riveting biography” which holds “…the reader’s attention from the first page to the last….” A Kings College lecturer praises Metaxas in the pages of the Wall Street Journal for his “…passion and theological sophistication….”

But it was the recommendation of friends with comments like this contained in an email: “if you haven’t picked up Metaxas’ Bonhoeffer book yet, its stinkin awesome” that had the greatest impact on my choice to read the book.

My only agreement with the reviewers, however, is that the book is indeed massive (550 pages). Beyond that, our opinions diverge.

Bonhoeffer indeed was a fascinating person, as the subtitle suggests. He was a man of deep and firm conviction whose devotion to his God led him to take action that both troubles and inspires us. He was a German Christian pastor and theologian who early on saw the evil in Hitler’s rise to power. He struggled deeply with how a Christian and the church should respond to the evils which we in retrospect can see so clearly. He chose a path of opposition and defiance. For his association with a plot which led to an unsuccessful assassination attempt on Hitler, he was executed at age 39 just two weeks before the war was over.

We respond to such a life. He was a faithful Christian, a devoted son, a passionate author, a humble servant of those in need. At his death he was engaged to be married to a young woman whom he had hardly had the chance to embrace, so thoroughly had the war separated them. To read of such a life is to reflect on our own and the choices we think we would have made, and the ones we do in our own point in history. Bonhoeffer challenges us all.

It is not just his life that matters here. It is the theology that motivated that life. Metaxas has stirred up a hornets’ nest of controversy regarding Bonhoeffer’s theology. “Eric Metaxas gives us a Bonhoeffer who looks a lot like an American evangelical…,” says one reviewer. Non-evangelicals tend to think that Metaxas is hijacking Bonhoeffer’s legacy and wresting him from the theologically liberal camp where they think he belongs. And so the battle rages.

Though Metaxas makes a good case I will let the theological battles be fought elsewhere. Whether he was or was not ‘evangelical’ is of little consequence to me. What matters to me is that in the reviewers’ zeal to address Bonhoeffer’s courage or to praise the book for its claiming him for ‘our side’, they overlook the fact that the book could have been so much better. As it is, the writing detracts terribly from the content. It seems to me that the book has received attention because of the interest of its subject and despite its stylistic and presentation flaws.

Metaxas’ slavish devotion to a chronological telling of Bonhoeffer’s life strips the vigor from the story. He strings together paragraph after paragraph, each of which is tied to the prior by chronological markers. Random references to places he stopped on his travels and gifts he bought for Christmas may be true enough in the chronology of his life, but such detail adds nothing to the story.

Further this bondage to chronology can kill the narrative drama. The last years of Bonhoeffer’s life were marked with plots and espionage and secrecy and threat, the stuff of novels. When the final attempt on Hitler’s life fails, Bonhoeffer is imprisoned and eventually killed. It could have been a grippingly told tale. However, because Bonhoeffer writes some things while in prison which are key in the theological controversies, Metaxas interrupts the narrative to engage the debate concerning these theological matters. Far better to tell the story of a man’s life through a series of overlapping thematic panels of content. A chapter on the theological controversies could tell one story while traversing a wide chronology, and then the story of the political intrigue could be told without interruption. I think only someone working on a doctorate in theology would feel that the book holds “the reader’s attention from the first page to the last…” It doesn’t.

Secondly, this tends in the distinct direction of hagiography (well critiqued here). Whenever we tell the story of someone we hold in high regard and with deep affection, it is hard to be objective about the subject matter. But we must be objective, and we must report the faults in a subject as well as his virtues. Did Bonhoeffer have faults at all? All men do, but his certainly are obscured if not completely omitted in this book.

Thirdly, I expect a biographer to tell the story of his subject by distilling the events and works of his life into a coherent narrative. Though Metaxas really aims at this, his effort is stymied by his over-dependence upon quoted material. Page after page is filled with quotes from letters and sermons and articles. One longish chapter has, by my estimate, 1260 total lines of text of which 590 (nearly half) are quotes. In fact, the biography ends with the entire manuscript of the sermon preached at his memorial service. Much of this is no doubt material worth preserving. But preserve it in an appendix. As it is, it bogs down the story by requiring the reader to do the distilling that is the biographer’s job.

Finally, Metaxas needs to ‘kill his darlings‘. Metaxas is so fond of clever turns of phrase that one loses sight of the seriousness of the story in the triteness of his language. Well turned phrases can enhance a story, but poorly chosen clevernesses detract. And they detract in abundance here.

At one point he says that Hitler “…would now with a flourish produce from his hindquarters a withered olive branch and wave it before a goggling world.” (356) From his hindquarters?

In speaking of the hopes attached to a plan to explode a bomb in a plane in which Hitler was flying, he walks through the events which “…would explode the bomb and then: curtains.” (427)

He tells of a church publication that had “…gone over to the dark side…” (325) Of the deal that Neville Chamberlain made with Hitler, “…it was ‘peace’ on the house, with a side order of Czechoslovakia.” (314)

Writing is hard. And harder still is it to write and then receive the insight of others as to how to improve one’s writing. And still harder is to be forced into making changes based upon the insight of another when that other is a clearheaded editor. I don’t blame Metaxas for the faults listed above. I blame his editor. A good editor would have forced him to address the stylistic weaknesses and would have reduced this from massive to manageable. A good editor, that is, could have made this into a book that was indeed “stinkin’ awesome”.

and scanned the blurb on the back, I knew I had my point of entry. A fantasy novel with baseball at its core – it begged to be read.

I’m not qualified or able to give a proper review of the book. Reviewers tend to suggest that the book fell short of its potential. As a ‘young adult’ fantasy, it is measured by a certain Hogwartian Wizard. The book was sometimes hard to grasp because so many of the creatures and characters had to be explained. Much new had to be learned before the pieces began to make sense. The pace picked up, however and I found myself well immersed in the last third and intrigued to see the end.

I’m not qualified or able to give a proper review of the book. Reviewers tend to suggest that the book fell short of its potential. As a ‘young adult’ fantasy, it is measured by a certain Hogwartian Wizard. The book was sometimes hard to grasp because so many of the creatures and characters had to be explained. Much new had to be learned before the pieces began to make sense. The pace picked up, however and I found myself well immersed in the last third and intrigued to see the end., or of the Bible itself.

And so I waited. And waited. And waited.

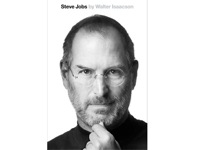

And so I waited. And waited. And waited.  Of course, not all the lessons are positive. Some are sober reminders of perspective. Jobs changed our world – about few can that be said – in ways I deeply appreciate. And yet, though he changed the world, I have to wonder: did he ever shoot hoops in the driveway with his son? Makes me reflect on my priorities.

Of course, not all the lessons are positive. Some are sober reminders of perspective. Jobs changed our world – about few can that be said – in ways I deeply appreciate. And yet, though he changed the world, I have to wonder: did he ever shoot hoops in the driveway with his son? Makes me reflect on my priorities.