Some months ago, the controversy du jour involved Vice President Pence’s policy of not meeting women alone. Some found his policy appalling, some found it quaint, and some found it proper. I weighed in on it here because it touched a bit of my own history and struggle as a teacher and particularly as a pastor.

In response to my post I received a kind and insightful email from a young woman whom I had had the pleasure of coming to know ten years ago. She is an intelligent and sensitive follower of Jesus who, as a woman, has had a difficult time finding a home in the church. In her email she shared her experience as a woman in churches similar to the ones I have pastored. I think we need to hear her, and others like her. (She has given me permission to post her comments, though I have edited them for brevity and anonymity.)

Neither she nor I bring these thoughts with any kind of agenda. But understanding the experience of others can implicitly suggest necessary agenda. If it does, I’m glad.

I am grateful for her honesty.

❦

When I first started to engage in Christianity, it was really clear to me that I would always be limited in some way as a woman. When [my male friends] had questions, they’d just go meet with the pastor. When I had questions, it was just not the same, even if that’s not an explicit rule. All the pastors were men and I’m a woman. So the natural supposition was to find a woman, but for many reasons that can be difficult.

To just know that’s not really an option when you have a male pastor, to engage as an individual and share your questions and concerns, subtly tells us “this is for men” and that women aren’t priorities here….

To be taught from a young age that my very biology is evil in some way, not because we’re all evil (total depravity!) but because I am a threat to men in some unknown way that I do not control, that I can be responsible for leading men astray, or that there’s a risk I’ll harm their reputation simply by being a woman, the internalizing of those messages is confusing and hard and leads to lots of feelings of self-hatred and questioning of yourself….

I had an experience of sexual abuse from a church leader as a child and so the argument that women are a risk to men is minimized when I know the opposite (that is, statistically more probable).

Going to church as a woman can sometimes be a heartbreaking experience. Every time I went to church with a male, whenever people would come over to say hi, he would be greeted first. He would be engaged in conversation. My presence there was in relation to the man next to me. There were a couple of times that I would try churches for weeks by myself and really wouldn’t make connections and then a guy would come with me and all of the sudden we’re welcomed. You can definitely make the case that the guys were just more outgoing and friendly, but it was definitely not every time.

Yes, these aren’t huge things. I’m not being stoned when I walk through the door or anything, but it is obviously discouraging to feel, even subtly, as if I don’t have a place because of my gender.

❦

I invite others to reflect on this and to share similar, or contrasting, experiences.

experience of being black in America, initial forays into that subject feel foreign to the student. It feels as if she has landed among an exotic people speaking a foreign tongue. The words are all new, and the questions being asked and explored are ones she has never before considered. A good student’s response will be to listen, to be quiet, to learn the language, and to hear how the questions are being answered.

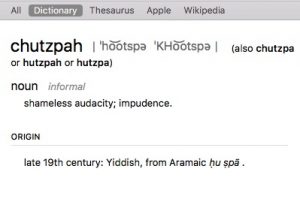

experience of being black in America, initial forays into that subject feel foreign to the student. It feels as if she has landed among an exotic people speaking a foreign tongue. The words are all new, and the questions being asked and explored are ones she has never before considered. A good student’s response will be to listen, to be quiet, to learn the language, and to hear how the questions are being answered. His response was predictable. “It takes a whole lot of chutzpah for you to walk in here and say that.”

His response was predictable. “It takes a whole lot of chutzpah for you to walk in here and say that.”

At 2 hours and 40 minutes Silence is hard to watch not because it is tedious, which it is not. It is hard to watch because it raises difficult questions of faith without offering easy answers to audiences uncomfortable with such questions.

At 2 hours and 40 minutes Silence is hard to watch not because it is tedious, which it is not. It is hard to watch because it raises difficult questions of faith without offering easy answers to audiences uncomfortable with such questions. My son’s Marine recruiter hung with him long after my son had signed his commitment papers. I later was told that Marine recruiters don’t get credit for the recruit until he steps onto the yellow footprints at Parris Island. Only then has he fully discipled his charge.

My son’s Marine recruiter hung with him long after my son had signed his commitment papers. I later was told that Marine recruiters don’t get credit for the recruit until he steps onto the yellow footprints at Parris Island. Only then has he fully discipled his charge. Published in 2016, Hillbilly Elegy shot to the top of many bestseller lists propelled by the thought during the last election cycle that reading it could help the mystified understand the American subculture that was Donald Trump’s base. Director Ron Howard thinks so highly of it that he plans to make a movie of it and it is among the top five books (three of which, intriguingly, are memoir) that Bill Gates recommends in his

Published in 2016, Hillbilly Elegy shot to the top of many bestseller lists propelled by the thought during the last election cycle that reading it could help the mystified understand the American subculture that was Donald Trump’s base. Director Ron Howard thinks so highly of it that he plans to make a movie of it and it is among the top five books (three of which, intriguingly, are memoir) that Bill Gates recommends in his  us die in childbirth, where innocent drinks become desperate addictions, where brilliant minds descend into dark caverns of mental illness. We live desperate for hope.

us die in childbirth, where innocent drinks become desperate addictions, where brilliant minds descend into dark caverns of mental illness. We live desperate for hope. At the heart of Disney’s 1973

At the heart of Disney’s 1973