Some of us live squarely, if unwillingly, in Nottingham. We live where those close to  us die in childbirth, where innocent drinks become desperate addictions, where brilliant minds descend into dark caverns of mental illness. We live desperate for hope.

us die in childbirth, where innocent drinks become desperate addictions, where brilliant minds descend into dark caverns of mental illness. We live desperate for hope.

If we pray, there are many paths along which those prayers could be shaped. The path followed by some of the Psalms led to imprecation, prayers wishing ill upon their enemies. Such prayers strike our gentle and sentimental sensibilities as too harsh and ill-fitting to be worn by Christians.That is, until we come face to face with our real enemies. Paul reminds us:

Put on the whole armor of God, that you may be able to stand against the schemes of the devil. For we do not wrestle against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers over this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places. (Ephesians 6:10-12)

We can puzzle over the effective power of the forces of darkness, but we ought never doubt that their efforts are arrayed to harm us. It is against THEM, the agents of death and decay, that we pray. Language that sounds violent and inhumane becomes understandable against such an enemy.

O God, break the teeth in their mouths;

tear out the fangs of the young lions, O LORD!

Let them vanish like water that runs away;

when he aims his arrows, let them be blunted.

Let them be like the snail that dissolves into slime,

like the stillborn child who never sees the sun.

Sooner than your pots can feel the heat of thorns,

whether green or ablaze, may he sweep them away!

The righteous will rejoice when he sees the vengeance;

he will bathe his feet in the blood of the wicked.

Mankind will say, “Surely there is a reward for the righteous;

surely there is a God who judges on earth.” (Psalm 58:6-11)

Awful words these, yes, but not when aimed at one whose food is the infliction of grief and death and suffering and despair. To pray thus negatively, is to pray this positively:

“Our Father in heaven,

hallowed be your name.

Your kingdom come,

your will be done,

on earth as it is in heaven. (Matthew 6:9, 10)

To the degree God’s will is not yet manifest on earth, we pray that it would be, that our understandable fear would be replaced by the certain hope of the coming kingdom.

We pray harsh words against a bitter enemy, all the while longing for this:

Be exalted, O God, above the heavens!

Let your glory be over all the earth! (Psalm 57:11)

Which is to cry out, with John and all the saints,

Come, Lord Jesus! (Revelation 22:20)

Such prayers are never lost upon the God who cares.

Especially in Nottingham.

At the heart of Disney’s 1973

At the heart of Disney’s 1973

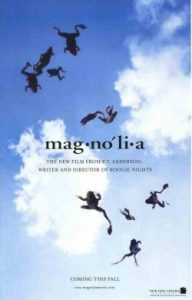

Issues that matter seem to be landing as profusely and as suddenly as the frogs in Paul Thomas Anderson’s remarkable film

Issues that matter seem to be landing as profusely and as suddenly as the frogs in Paul Thomas Anderson’s remarkable film

Among the many things I might say, that sentence is one which could probably get the most universal affirmation. Bad stuff has happened. The year that is past seemed to feed us an over-the-top diet of death and violence and loss and disappointment. I have seen many online express a longing for this year to be gone, a longing I sincerely get.

Among the many things I might say, that sentence is one which could probably get the most universal affirmation. Bad stuff has happened. The year that is past seemed to feed us an over-the-top diet of death and violence and loss and disappointment. I have seen many online express a longing for this year to be gone, a longing I sincerely get. For nearly fifteen years, my wife and I, our children, and now our grandchildren have spent a week camping in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Wealthy people have summer homes. We have tent pads and cook stoves. But it has been a precious way for us to stay connected and build memories together. We could tell you of the night we almost died (or thought we would), or the time in desperation we ‘made’ a shower, or the time and place where our (now) son-in-law proposed to our daughter. This is OUR summer home, albeit one we share with nine million others each year.

For nearly fifteen years, my wife and I, our children, and now our grandchildren have spent a week camping in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Wealthy people have summer homes. We have tent pads and cook stoves. But it has been a precious way for us to stay connected and build memories together. We could tell you of the night we almost died (or thought we would), or the time in desperation we ‘made’ a shower, or the time and place where our (now) son-in-law proposed to our daughter. This is OUR summer home, albeit one we share with nine million others each year.