Recently, tear gas canisters were launched at people near the U.S. border with Mexico. The targets were those fleeing Central American instability to seek asylum in the United States. They were and are people.

And some of them were children.

No decent person wants to gas children, of course. But I wonder to what degree the language of our arguments, to the degree that it dehumanizes others, allows some to take such action which leaves children in the crossfire. That is, ‘migrants’ or ‘refugees’ might be met with a degree of sympathy and compassion. ‘Criminals,’ ‘threats,’ ‘rapists,’ and ‘terrorists’ (all terms at one point used to reference those heading for the border), on the other hand, are more readily cannon (or tear gas) fodder. The more successfully our language moves a group from the category of ‘human’, the easier it becomes to justify violence against them.

To counter this tendency, we need to read more books.

❦

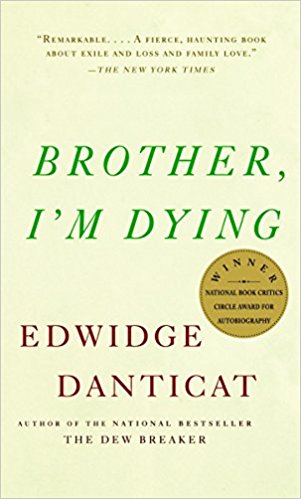

At the 2018 Festival of Faith and Writing my wife discovered the books of Haitian writer Edwidge Danticat. With her encouragement I eventually read two of them, both set in Danicat’s native Haiti. I’ve never been to Haiti and I benefited from her rich and unsentimental portrait of a people shaped by their land and history to be so different from me and yet, by our shared humanity, to be so similar. Months later, the flavor of that land, its richness and earthiness, and of that people, their luminescence, joy, and sadness, is still with me.

The urge to leave such a place for greater opportunity or safety is developed in Danticat’s moving memoir of her father and uncle, Brother, I’m Dying. When Danticat was a child of two her father immigrated to the US, followed shortly thereafter by her mother, leaving Edwidge to be raised by her aunt and uncle. Such was the family-separating immigration policy of the time.

When at age twelve her parents were able to bring Edwidge to the U.S. to be with them, she was forced to leave the only land she had known and the uncle who, through disability and poverty, had cared for her. It was painful, as such things always are for people. People, and these are people, after all, like us, never make such decisions lightly.

In time, her uncle, then an old man suffering from a debilitating but treatable disease, fell under the disfavor of a violent gang. He was forced to flee Haiti seeking safety and asylum in the U.S. Danticat’s well-researched and well-documented account of her uncle’s experience with U.S. immigration authorities is agonizing to read and illustrative of a system that is and has long been broken and in need of repair.

It is a system that dehumanizes and eventually lofts tear gas across border walls.

❦

Will reading Danticat, or authors like her, shape or change, a reader’s convictions regarding immigration policy? I can’t say. What I can say is that our convictions will be better formed when we form them around the fact that the subjects of these convictions are people. Not problems, not enemies, not threats, but people.

They are all people. And that matters.

Adria Bautista

This is expertly spoken, thanks Dad.

Randy

Except, of course, for the fact that in the initial posting, I misspelled Ms. Danticat’s name a half dozen times. Kind of throws the ‘expert’ label into dispute. But thank you!

Gail Landis Brightbill

Yes, thank you!

Suzanne

“They are all people. And that matters”

Well said.

Roy Starling

Yeah, well where would this Great Nation be if we had called Native Americans-American Indians-Indigenous Tribes “people”?

Randy

What? Instead of ‘savages’? Point well taken.