Over half of my thirty years of pastoral ministry have been deeply marked by the refreshing vision of pastoral ministry embodied by Eugene Peterson and given expression in his books, particularly The Contemplative Pastor and A Long Obedience in the Same Direction. His sense of pastoral vocation affirmed for me a focus on pastoral care and the weekly rhythms of congregational life. He came to me as a freeing mentor delivering me from ministry models majoring on ways to grow a church. His affirmation in many ways has saved me from burning out and giving up. His is a critical voice for those called to be ordinary pastors.

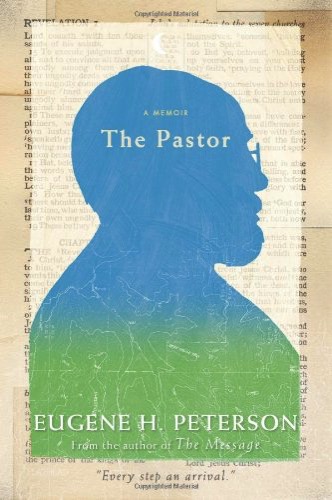

So when a friend recently mentioned that he was reading and enjoying Peterson’s 2011 memoir titled simply and profoundly The Pastor, my heart ached to read it. Perhaps I should have tempered my fan-boy expectations, for I came away disappointed and sadly unsatisfied.

Peterson is foremost a story-teller, and this book is best when he simply tells his story. When freed to tell his stories, he soars. But then he attempts to apply them or draw a moral from them, and the wind falls from beneath the wings. This is more an exposition of his pastoral theology with his life and that of his congregation serving as extended illustrations of the pedagogical purpose. There is a place to develop a pastoral theology. Just don’t call it memoir. It feels as if he has begun to no longer trust his reader to draw the lessons he feels can be learned from his life, and so he insists on telling, and not just showing, and this detracts from the whole.

But unquestionably the greatest flaw is the book’s lack of transparency. Too much is hidden and unsaid. This is fatal in a memoir.

The pastors I know struggle. We struggle with doubt, with disappointment, with anger, and we feel these things intensely. A pastor’s heart is often broken. We disappoint people, we make mistakes, we worry, we question, we hurt and are hurt. How can this book about a pastor’s life be genuine and real without stories of heartache and rejection? A pastor’s life without darkness does not sound like any pastor I know. The only glimpse we have of Peterson’s emotional life are the tears at his mother’s funeral.

Of course, ministry has joys as well. When he speaks of joy in ministry it comes across as clinical. He speaks of his writing, but he says nothing about the thrill of being published, nothing about the agony or prospects of rejection, nothing of his writing habits, little of the tension between his writing and his pastoral ministry. It’s all very theologized, and in fact, boring for those who want to know both what is it like to be Eugene Peterson and what it might be like to be a pastor who also writes.

The lack of honesty tilts to a kind of boasting which conflicts with the humility I’ve come to expect from Peterson. A number of the sections begin with his analysis of weakness in a pastoral model, or a way of ‘doing church’, and then proceeds to show how he, and his church, got it right. This is off-putting, and feels false.

But maybe he was different? I don’t think so. The final three pages of the book is a letter he wrote to a young pastor. Here alone, at the end, we see hidden references to the honesty lacking from the rest of the book. He speaks to this young pastor of not knowing what to do, of making mistakes, and of ‘faithless stretches’. This feels real, like the vocation I inhabit. But he says nothing more about it, and that is the glaring hole at the center of the book.

This is not a bad book. Eugene Peterson is not capable of writing a bad book. But it does not feel honest or true to its genre, and that makes it uninteresting, and that, in the end, makes me sad.