It is among the virtues of evangelical thinking to frame one’s life and practice according to Biblical standards. At the heart of evangelical discussions will always be the core question: are we reading our Bibles correctly? This is the question that Aimee Byrd raises in her recently published Recovering from Biblical Manhood and Womanhood: How the Church Needs to Rediscover Her Purpose. Byrd offers this book as a contribution to the discussions in the evangelical world about how men and women are to relate to one another in the church and in the world. To ask whether we are reading our Bibles correctly with regard to men and women is a question worthy of consideration and discussion.

❦

In her book, Byrd challenges many of the premises and conclusions of the evangelical Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood (CBMW), an organization that has shaped for many evangelicals what it means to be a Christian man or woman. The impact of the CBMW has been broad and deep and, to Byrd, problematic.

While clearly embracing her church’s traditional and confessional understanding of office and gender, Byrd challenges many of the assumptions and formulations of the CBMW. She questions the theology lying behind their primary assertions and challenges their use of Scripture. Positively she makes a Biblical case to see women as equal participants and contributors to the life of the church and society. Men and women, she argues, equally bear the image of God and have gifts and ministry to share with one another.

Even when critical of others, she is respectful. Her exegesis is compelling. Her insights are properly provocative. Her call to return discipleship to the local church is refreshing. She writes well and with temperate language, and she invites others into a conversation on the matters she raises.

❦

Readers may assume that I am compelled to speak favorably regarding Byrd’s book because she endorsed my book Something Worth Living For. Grateful though I am for that, I speak positively because this is a worthy book raising necessary questions. Her arguments invite engagement.

The responses she has received, however, at least by the loudest voices, have been completely other. Some warn that she is leading the church onto a dangerous and slippery slope (always a weak and tenuous argument). She has been mocked mercilessly. She has had speaking engagements sabotaged by slander. Instead of interaction on substance, she has received misogynistic slams against her looks, against her husband, and against women in general. Such behavior is inexcusable and repugnant. Apparently while battling for the Bible some evangelicals lost sight of the Christian virtues of charity and gentleness.

This book, and others like it, are met with such a response because, at root, evangelicals are a fearful bunch. Fear is evangelicalism’s ‘F’ word. It is not often spoken or faced. And it reveals that try as we might, evangelicals really have not moved away from their fundamentalist roots.

❦

Evangelicals today laugh at the stereotype of the fundamentalist. Evangelicals dance and drink and smoke cigars and pipes, and even make occasional judicious use of the other, less socially acceptable, ‘F’ word. And yet, they, too, are moved by the same fear that led to the prohibitions they now consider foolish.

It’s worth imagining for a moment why drinking and dancing and card playing were forbidden in the first place.

If there is a dangerous pit on one’s property, judicious landowners build a fence around it. Fearful ones build the fence a mile away. Such fear led to the prohibitions evangelicals mock. Dancing could become erotic and the erotically roused may not be able to resist sleeping together. Better build the fence further out. Fear of sin, sexual immorality, led to the forbidding of otherwise non-sinful behavior, dancing. Fear led our fundamentalist forebears to forbid that which was permitted in order to guard against that which was forbidden.

Similarly, to prevent sinful drunkenness drinking itself was redefined as sin. Gambling can be a violation of the eighth commandment so, to be safe, card playing was forbidden. Fear of the thing forbidden led to forbidding a thing permitted.

Evangelicals now dance and drink and play cards having learned that while it is sinful to permit a forbidden thing, so too it is wrong, even sinful, to forbid a permitted thing.

But one may ask how much have we really learned. We might still be in the habit of forbidding what is permitted out of fear that we would permit what is forbidden. In many churches, women are not to receive the church offering. They are allowed to teach boys, but teaching adult men is forbidden. They are not to lead a mixed small group Bible study. They are not to be present when church elders debate matters affecting the entire church. They certainly should not write books addressing matters of theology or church practice.

The issues, whatever they are, whether it is enjoying a lager or allowing a woman to pray in public, should be discussed. But fear shuts down the discussion. The camel’s nose cannot be allowed under the tent. Slippery slopes must be avoided. Prohibitions become entrenched, and fear does not allow them to be questioned. If a woman is allowed to participate in the offering she’ll soon be presenting herself as a pastoral candidate.

I wonder how much abuse was heaped on the first evangelical pastor to offer his elders a beer? Someone along the way had the courage to ask, “Are we reading our Bibles correctly?” We should never be afraid to ask that question. Aimee Byrd is asking that very question and the response has been swift and severe and motivated undeniably not by reason but by fear.

❦

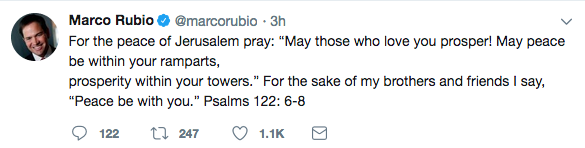

One of Aimee Byrd’s more respected critics, Southern Baptist Seminary professor Denny Burk, suggests that her questions be given the treatment that Gamaliel, the rabbi and mentor of Saul of Tarsus, recommended be given to Peter and the other apostles in the first century. He suggests she be ignored, marginalized, and dismissed. Any who want to remain safely distant from the slippery slope should just ignore her. Plus, if ignored, she will go away. He says, “. . . bad arguments, even when brilliantly presented and popular in their moment, don’t last. Where are Rob Bell and Donald Miller today? And their arguments? The world has moved on . . .”

Such advice dovetails so nicely with Gamaliel’s in Acts 5:35-38 that I can’t resist a mashup:

And Dr. Burk said to them, “Take care what you are about to do with this woman. For before these days Donald Miller rose up, claiming to be somebody, and a number of people joined him. He was ignored and all who followed him were dispersed and came to nothing. After him Rob Bell the Universalist rose up and drew away some of the people after him. He too faded off the evangelical scene, and all who followed him were scattered. So in the present case I tell you, keep away from this woman and let her alone, for if this plan or this undertaking is of man, it will fail.”

It is clearly mistaken and unfair to put Byrd in the same company as Donald Miller and Rob Bell (guilt by association is as easy as “slippery-slopism”). Byrd’s commitment to the church and her confessional heritage is deep and should be unquestioned. There is really no legitimate comparison here.

Dr. Burk is mistaken in another way. The questions Byrd raises are not going away and should not be written off so cavalierly. Her basic question is evangelical to the core: are we reading our Bibles correctly?

One who asks such a question well is a gift, not a threat, to the church. Byrd has framed the questions that many in the church are asking but can’t. She has done so clearly and respectfully and to engage her is to accept the gift.

But many won’t. Perhaps they are afraid.

Perhaps they fear she may be right.

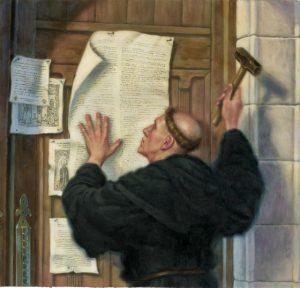

The slippery slope is, to many, a place no one committed to orthodoxy and historic Christian doctrine should ever be found. But Brother Martin never got that memo. So with a few quick strokes of the hammer, he ventured onto it. And yet we honor him five-hundred years later while we excoriate others who follow in his footsteps today.

The slippery slope is, to many, a place no one committed to orthodoxy and historic Christian doctrine should ever be found. But Brother Martin never got that memo. So with a few quick strokes of the hammer, he ventured onto it. And yet we honor him five-hundred years later while we excoriate others who follow in his footsteps today. His response was predictable. “It takes a whole lot of chutzpah for you to walk in here and say that.”

His response was predictable. “It takes a whole lot of chutzpah for you to walk in here and say that.”

My son’s Marine recruiter hung with him long after my son had signed his commitment papers. I later was told that Marine recruiters don’t get credit for the recruit until he steps onto the yellow footprints at Parris Island. Only then has he fully discipled his charge.

My son’s Marine recruiter hung with him long after my son had signed his commitment papers. I later was told that Marine recruiters don’t get credit for the recruit until he steps onto the yellow footprints at Parris Island. Only then has he fully discipled his charge.