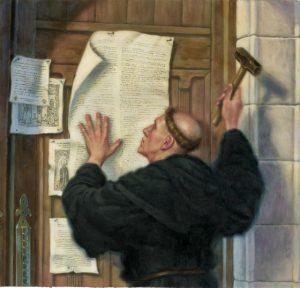

On October 31, 1517, Martin Luther took one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind, onto the slippery slope.

The slippery slope is, to many, a place no one committed to orthodoxy and historic Christian doctrine should ever be found. But Brother Martin never got that memo. So with a few quick strokes of the hammer, he ventured onto it. And yet we honor him five-hundred years later while we excoriate others who follow in his footsteps today.

The slippery slope is, to many, a place no one committed to orthodoxy and historic Christian doctrine should ever be found. But Brother Martin never got that memo. So with a few quick strokes of the hammer, he ventured onto it. And yet we honor him five-hundred years later while we excoriate others who follow in his footsteps today.

Defenders of slippery slope alarmism will take issue with my suggestion. It is frequently suggested that this slope leads only to ruin. Therefore, Luther’s act was one of courage, not slippery-slopism. I don’t deny his courage. It is always courageous to take a step that puts one at odds with one’s peers. But to advocate for change when change is needed always puts one on a slippery slope, and that, as it was with Luther, is a good and necessary thing.

One concerned writer, in a lament over the descent into liberalism of a previously orthodox minister and as a caution to any who would venture onto the slippery slope that led him there, defines the slippery slope as “the unstoppable descent into liberalism and unbelief that begins when the authority of Scripture is compromised out of cultural accommodation.” He then maps the route to that slope: “In the late-20th century and early 21st century, the slippery slope has tended to begin over the issue of women’s ordination.” At this point of cultural accommodation, he suggests, the slippery slope begins. The slope, being slippery, inevitably sends one careening to the pit of ultimate unbelief. He jokingly (I think) presents his case as example number 4,742.

Would I win if I could produce 4,743 examples of those who took that step and did NOT descend into unbelief? Taking this issue of the ordination of women alone, often those who have embraced a change on this (I am not one of them, if that helps) have done so as a result of listening to the voices revealing skewed treatment of women in the church. They have revisited Scripture to see if somehow their previous reading had been wrong. One may not agree with their conclusions. But we must accept that there is a time when we need to be awakened to our mistaken views and have them corrected by scripture even if it means taking a stand against the ecclesiastical powers that surround us. I think Martin would agree.

We who celebrate the Reformation have a motto supporting this idea: Semper Reformanda. This motto calls us to be sufficiently humble regarding our convictions that we are willing to constantly submit them to the scrutiny of scripture. Yes, to face the possibility of error and to suggest possible correction is to step onto a slippery slope. That does not always lead to unbelief. It sometimes leads to necessary change.

The slippery slope is a dangerous place to be, for sure. But it is not always the wrong place to be. Far more dangerous is to refuse ‘being reformed according to the Word of God.’

Let’s engage those on the slippery slope, let’s hear them, let’s learn from them, let’s examine the Scriptures with them. But let’s not dismiss them.

One of them might be named Martin.

Brightflash

!!! Nice, Randy!