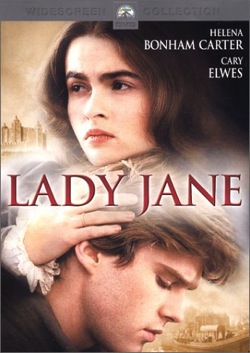

In my sermon this past Sunday, I made mention of the period of England’s history in which Edward VI was dying, and others were scheming to retain power by arranging for young Lady Jane Grey to be his successor. (This is all wonderfully captured in a movie called simply Lady Jane which is, unfortunately, very expensive to buy, but can be streamed.)

In the midst of this intrigue, a young John Knox was given opportunity to preach to the parties involved. He made the most of his opportunity.

The second Sunday in April 1553 the last Tudor King of England went to hear, for the last time, one of his favourite preachers in Westminster Abbey. All the glitter and jingle of a medieval court was there; the glorious, flashing colour, the shields and banners, the velvet and miniver. His Highness Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, a gorgeous figure, famous as a jouster, with his tall handsome sons: Paulet, Marquess of Winchester, the perfect time-server, who was Comptroller, Secretary and Lord Treasurer to Edward, who cursed Mary as a bastard, yet lived to ‘crouch and kneel’ successfully to her in turn; all the dukes and earls and jewelled ladies were there: for sermons were high fashion, for the moment, in England.

Knox, the dour little Scotsman, rising to preach, perhaps looked round from the white-faced boy to the jealous lords: and gave out his text from the Gospel of St. John xiii. 15: ‘He that eateth bread with me hath lifted up his heel against me.’

These words, used by the Lord at the Last Supper, are quoted from Psalm 41, v. 9, in which David laments the treachery of Absalom. Knox turned back to read again those incomparable stories of treachery and heroism in Isaiah, in 2 Samuel xvi and xvii, 2 Kings xviii; stories of three different sorts of traitors: of Shebna the traitor who wormed his way into King Hezekiah’s confidence, becoming comptroller, secretary and treasurer – did the congregation prick up their ears? Of Achitophel who rose to be the highest in the land while he plotted with Absalom to supplant David: whose counsel ‘was as the oracles of God’: of Judas who sold his friend.

The preacher’s voice rose to a climax: ‘Was David and Hezekiah, princes of great and godly gifts and experience, abused by crafty counsellors and dissembling hypocrites? What wonder is it then, that a young and innocent King be deceived by crafty, covetous, wicked and ungodly counsellors? I am greatly afraid that Achitophel be counsellor, that Judas bear the purse and that Shebna be scribe, comptroller and treasurer.’

There must have been a wave of anger – perhaps of laughter – along the gorgeously dressed congregation. Was there too a flicker of satisfaction over the white face of the little King? But whether or not he was the King’s favourite, this sermon went a little too near the bone : Knox was summoned before the Privy Council of England on 14 April.

There were present at this Council, Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, the Lord Chancellor, the Earls of Bedford, Northampton and Shrewsbury; the Lord Treasurer (‘Shebna’), and the Lord Chamberlain, and two Secretaries of State. For obvious reasons, they did not take him up on the sermon; but instead brought up the old complaints against him. Why had he refused preferment? Why had he objections to kneeling, to the special wafer instead of common bread, and the like? Knox had answers ready for all their points: so in the end they ‘dismissed him with fair words’, saying only ‘they were sorry to understand he was of a contrary mind to the Common Order’….

His enemies could afford to wait a little. The sands were clearly running out for Edward. Youth had ceased to fight with death: his days were numbered.

— Plain Mr. Knox, Elizabeth Whitley

This scene, unfortunately but not surprisingly, does not make it into the movie.