Needing a break from the fairly heavy reading of A Distant Mirror and The History of the Ancient World

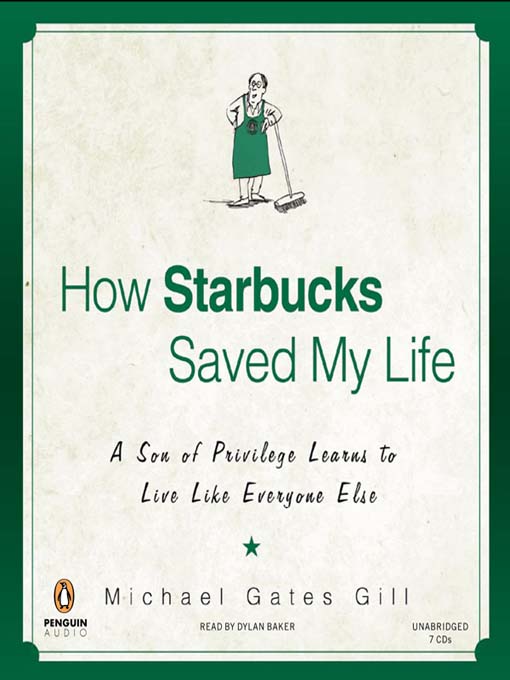

, I was glad to receive for my birthday from my son and daughter-in-law the book How Starbucks Saved My Life

by Michael Gates Gill.

A friend had been recommending this book to me for some time. It is a book that could be enjoyed and tossed aside without much of a thought. However, there is more here of value than one might at first imagine.

The book’s subtitle rightly casts Michael Gates Gill as a son of privilege. His father was a writer for the New Yorker, his Yale education was a matter of course, and his rise to prominence in a major New York advertising firm partially due to the connections his background afforded him.

But at around age 60, it all fell apart. He was fired from his job (younger men were cheaper and just as capable) and he lost his marriage (due to an affair he now sees as foolish) and, in due time, his fortune. Trying still to maintain some semblance of success, he was sipping a latte at a New York Starbucks one day when the African-American manager offered him a job.

Being desperate he took the job. The story unfolds from there. He who in his previous life would argue against the expectations of affirmative action found himself working for a black woman whose mother had been a drug dealer, and alongside of men and women he would have barely noticed much less trusted before. And it all morphs into the happiest time of his life.

Starbucks was the context for Gill’s transformation, and much about the Starbucks culture contributed to his transformation, but the points at which his transformation occurred transcend Starbucks and expose tendencies many of us need to examine. One example will suffice.

Gill is honest about his elitist and arrogant treatment of those unlike him. He was a man who had in his life met the likes of Ernest Hemingway and Jackie Kennedy and was used to treating underlings as capital to be spent and cast aside. At Starbucks, however, he began to see those who were once ‘invisible’ and ‘dispensable’ as real human beings.

One night, he was closing the store with two African-American partners, Charlie and Kestor. When their work was done, they got ready to head to the subway together.

“Kester and Charlie were changing into their street clothes: do-rags, big caps, baggy pants, and boots. They were completely transformed from the smiling Partners in green aprons. They both had earphones dangling down their chests. When I went back upstairs, I was accompanied by two guys who I would have at one point typed as hip-hop artists or gangsters—probably both. But now I knew when I saw guys like these, they might be something else, too. They had lives and loves that were as full or fuller than mine.”

Gill had to fall to see what many of us do not see yet. We look at people and type them: gay, atheist, bitter, happy, homeless, buddhist, liberal, Republican. Once we type them, we fail to see them as real people. They are merely categories about whom we form blanket opinions.

It was no coincidence that I was reading this alongside my study of John 4, where Jesus crosses gender, lifestyle, racial, and religious barriers to do what no one else was doing: treating a sinful Samaritan woman as a real person. May his grace so infiltrate our souls so that we might do the same, see others as people having “lives and loves that [are] as full or fuller than” our own.