This past Sunday night, Hope Presbyterian Church, the church I pastor, shared a worship service with our friends at St. Paul Missionary Baptist Church. We will do the same this Thursday, Thanksgiving morning, which is for our two churches, an annual affair. Hope is predominantly white; St. Paul predominantly black.

As much, though, as we enjoy these times of cross cultural fellowship, we all are realistic enough to know that our worlds, black and white, are simply intersecting at these times. We do not live in each other’s worlds, and we don’t understand each other’s worlds.

As much, though, as we enjoy these times of cross cultural fellowship, we all are realistic enough to know that our worlds, black and white, are simply intersecting at these times. We do not live in each other’s worlds, and we don’t understand each other’s worlds.

To cross that bridge to understand would require a type of immersion that few of us will ever experience. To read about one who made that transition cracks a window into that world, ever so slightly, and yet positively so.

A few months ago, in a random conversation with a woman at a Starbucks, a woman, recently retired as a librarian at a local high school, directed me to a book which is apparently often assigned in schools. The book is called The Color of Waterand subtitled “A Black Man’s Tribute to His White Mother.” The subtitle captures what the book is about.

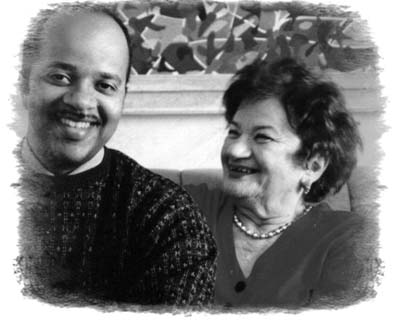

James McBride is a journalist and musician who is one of twelve children born to Ruth McBride Jordan. Ruth was born Rachel Deborah Shilsky. She was raised by her Jewish parents (her father was a rabbi turned shop keeper) in a Virginia town that did not like Jews any more than it liked blacks. Rachel was so traumatized by the experiences of her childhood, not the least of which being her domineering, abusive father, that she would never speak of it, until prodded by her grown son.

When she married a black man, this white Jewish girl was considered dead to her Jewish family. Changing her name to Ruth, to obscure her background, the couple moved to New York and began to raise a family. Her husband died after 16 years of marriage, but not before Ruth came to trust in Jesus, a trust that was real and sustaining for her (and celebrated in the book). In that time the couple jointly founded a church which her husband pastored and, along the way, they became the parents of a brood which would eventually number 12 (some born to Ruth’s second husband).

When she married a black man, this white Jewish girl was considered dead to her Jewish family. Changing her name to Ruth, to obscure her background, the couple moved to New York and began to raise a family. Her husband died after 16 years of marriage, but not before Ruth came to trust in Jesus, a trust that was real and sustaining for her (and celebrated in the book). In that time the couple jointly founded a church which her husband pastored and, along the way, they became the parents of a brood which would eventually number 12 (some born to Ruth’s second husband).

The family was raised in the neglected projects of NYC, but Ruth was a woman who would not allow that to be the downfall of her children. Taking advantage of every cultural offering one could grab and using every tool available to get her children into the best possible public schools, this woman made it happen. Though she lost direction after the death of her second husband, all of her children not only went to college, but two became doctors and one a PhD professor chemistry, along with the journalist-author, nurses, and other professionals. It’s an amazing, though often sad and painful story.

I will never enter that world. I will never be black, or Jewish, or amazingly both at once. I will never know the anguish of living in fear simply because of the color of one’s skin or the ethnic heritage one has inherited. I will never know the racial confusion that one raced in this setting is forced to confront.

But this is one of the reason we read books. McBride has cracked the window to allow me to peer into his experience and that of his mother, to glance at their worlds. If this helps me to better understand the worlds of those friends with whom we worship on Thanksgiving and other times, then the read has been worth the time spent.

Staci Thomas

My mom has raved about this book for years. She keeps encouraging me to read it. It is going to the top of the list now.Staci

Gus/Adri

Thank you for the reminder; I read the book some years ago but had forgotten much about it.This quotation from novelist William Styron (1925-2006) seems fitting: "A great book should leave you with many experiences, and slightly exhausted at the end. You live several lives while reading it."–ae